They say the first race happened as soon as the second car was built – but that’s not entirely true, as most of the earliest automobiles came into existence hundreds of miles apart. The earliest motorsports drew their inspiration from Bertha Benz’s “reliability run of August 5th, 1888, which proved that an internal-combustion engine car could cover useful distances. By the turn of the century, however, people were itching to race wheel-to-wheel.

In Europe, it was a simple matter to close public roads and compete on routes from town to town; over here in the States, however, the earliest motorsports made use of the many horse-racing spectator ovals instead. That, in a nutshell, is why Europeans venerate Le Mans and Monaco while we adore Indianapolis and Talladega. We’ve selected some great moments from both traditions, along with a few photographs to set the mood.

Joe Dawson Wins the Indy 500, 1912

When Ralph DePalma and riding mechanic Rupert Jenkins lost a connecting rod on lap 198 of the 1912 Indianapolis 500, they also lost the lead – but not immediately, as they coasted to the back stretch of lap 199 then began pushing their Mercedes towards the start/finish line. In short order, however, they were passed by the National racer of Joe Dawson and Harry Martin, who set a long-standing record for fewest number of laps led by a winning driver. At 22 years and 323 days of age, Dawson was also the youngest winner in “500” history and would hold that accolade until 1952, when Troy Ruttman bettered him.

Indianapolis Motor Speedway was, and remains, a unique part of racing history. With 3.2 million paving bricks, a 2.5-length that exceeds many road courses, and its infamous location in the “company town” of Speedway, Indiana, it remains as vital today as when the bricks were laid 114 years ago. One difference, of course: the checkered flag is no longer waved within spitting distance of a roaring 600-cubic-inch open race car.

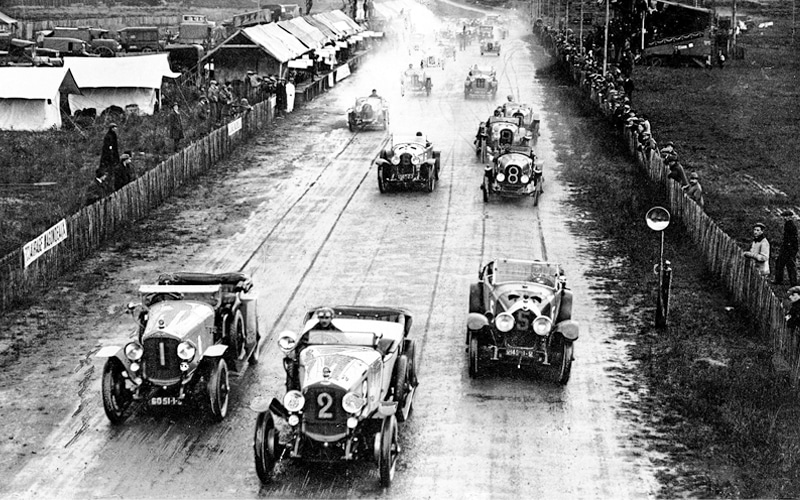

LeMans Becomes a Race, 1923

It was just meant to be a reliability run. By the early 20s it was common for European manufacturers to engage in mutual demonstrations of automotive endurance that wound through town and countryside. These events were part advertising and part spectacle, and in many cases the first-time a given hamlet or village would see a proper automobile.

LeMans was intended to be different, since it would follow a regular course and run for twenty-four hours in a row. “Winning” the event meant offering the best performance on a complex scale with nearly arbitrary weighting for engine size and other factors – but as soon as it started, the spectators realized that this would, in fact, be a race.

A Chenard-Walcker (no longer available in dealerships, alas) completed 128 laps in the 24 hours, but 30 of the 33 cars finished. The organizer, France’s ACO, was satisfied that the further potential of the automobile had been demonstrated. The prize? A chance to win the Rudge-Whitworth Triennial Cup, which much like the Schneider Trophy in aviation, needed to be claimed thrice in a row to be possessed. From then on, however, all pretense of reliability-running was dispensed with, LeMans was now a motor race.

The Original Watkins Glen, 1948

From the very start, American road racing had a faintly aristocratic air about it. The newly born Sports Car Club of America took itself very seriously; one could be disqualified or “blackballed” in much the same way that prospective Skull & Bones members at Yale might be. When Cameron Argetsinger decided to follow the European model and hold a sports-car race on public roads, it took a lot of heavy hitters, both local and national, to make it happen in the quiet town of Watkins Glen, New York.

The original course was 6.6 miles, and it ran down the main street of Watkins Glen before tearing out into the farmlands up the hill and away from town. As in Europe, spectators stood inches from the action. Young and wealthy social register types did battle with scrappy ex-Gis, with little quarter given. Sam Collier died while leading the race in 1950, but it was the death of a 7-year-old spectator in 1952 that forced the organizers, and the SCCA, to ponder the fate of road racing in the United States. Their eventual answer – the Watkins Glen “road course” outside town – would set an example for new track operators and racing clubs nationwide.

Monaco Restarts Post-War, 1948

Half a year before road racing came to Watkins Glen, it returned to the streets of Monaco. This was no mean feat at a time when much of Europe was still short on bread and basic necessities. A new formula pointed out further differences between the Continent and the New World; 4.5 liters normally aspirated or 1.5 liters supercharged would be the maximum engine capacities. Much of the engineering was still very much pre-war, with the winning car being an Alfa Romeo that debuted in 1939. Also, a bit pre-war: the winning driver, 41-year-old Giuseppe Farina.

For the next 30 years, Formula One would be an uneasy competitor to, and occasionally deficient in prestige to, big-bore road racing in Europe. It would take several technological leaps and major manufacturer involvement to lift F1 into its current position as the world’s premier motorsport – but now, as in 1948, the Monaco GP is its signature event.

Drag Racing Comes into Its Own, 1950

Arguably the most American form of racing ever conceived, drag races were commonplace in California and elsewhere before World War II. There was little interest in formalizing these meets, which suited most drag racers just fine. In 1950, however, the Southern California Timing Association, which had been sanctioning top-speed events since 1937, came up with the idea to use a decommissioned Marine blimp base near Santa Ana, CA, for head-to-head races.

The early events were rolling starts towards a flagman, after which the two drivers would head a quarter mile down to the photocell timers. Elapsed time was the measure of victory, not top speed – this was new, and it changed the game for American racers who had long thought of max-velocity as the only valid way to pick a winner.

Like their cross-country compatriots in the SCCA, the SCTA was picky about what could race, and how. It didn’t matter. Pretty soon, there were purpose-built dragstrips throughout California and heading east in a hurry. The American motorsport was expanding at full throttle.

The “Kiss of Death”, 1957

Michael Mann’s newest movie, Ferrari, dramatizes the 1957 Mille Miglia and the death of Alfonso de Portago at 150 miles per hour in a Ferrari 335S – but one part of it required no dramatization, because it was true to life. Portago’s companion of the moment, actress Linda Christian, leaned in to kiss him during the fuel stop before his crash. Had everything gone as planned, it would be remembered as the exuberant act of two young people on top of the world in every sense. Instead, it serves as a reminder that the specter of death is never completely absent from motorsport. Not in 1957, and not today.

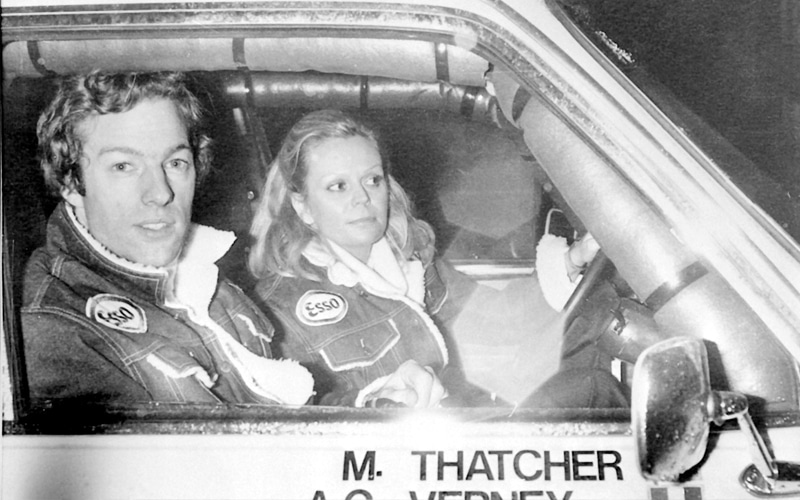

Mark Thatcher Goes Missing, 1982

The Paris-Dakar rally was just a few years old in 1982, but it was already at the forefront of European consciousness as a glamorous but deadly event. Which is perhaps why Mark Thatcher, son of the British Prime Minister, decided to run a Peugeot 504 as part of a three-person team. Having run Le Mans in 1980 and 1981, albeit without success, Thatcher didn’t think he needed much, if any, preparation for Paris-Dakar. And how hard could it be to drive a Peugeot 504, which already had a reputation as being an unbreakable way to get across Africa, up and down a few sand dunes?

Turns out it was more than Thatcher and his team could handle. They got lost and were found dozens of miles off the beaten path by an Algerian Air Force pilot five days after being reported missing. If it humbled Thatcher, he didn’t show it. And it made the rally an international spectator destination, with as many as 50,000 people waiting for each stage the following year.